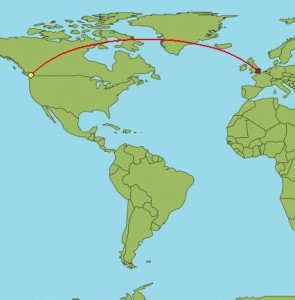

One of the better pieces I have read on Long Distance Relationships (LDRs) is this 2006 article by Mary E. Morrison entitled “How To Make Long-Distance Love Work“. You will undoubtedly – if you are interested – eagerly devour said piece in its entirety yourself, but for those with little time to spare (most of us these days it seems!) here are some selected extracts.

One of the better pieces I have read on Long Distance Relationships (LDRs) is this 2006 article by Mary E. Morrison entitled “How To Make Long-Distance Love Work“. You will undoubtedly – if you are interested – eagerly devour said piece in its entirety yourself, but for those with little time to spare (most of us these days it seems!) here are some selected extracts.

With reference to her own LDR Ms Morrison writes:

‘Instead, we spent three months communicating through emails, text messages, and, yes, quick phone calls, usually about the most prosaic of things. As it turns out, that’s one of the surest ways to a successful LDR.

Here’s why: When psychologists talk about intimacy, they’re generally referring to two components. The first is the ability to verbalize fairly deep vulnerabilities—for instance, to say “Do you love me?” and “I miss you.” The trickier, almost subconscious part is maintaining the feeling of being intermingled in your partner’s life, a state the experts often refer to as “interrelatedness.” Couples that are geographically close establish this by discussing the mundane details of daily life, whether it’s the fact that you had to take a different route to work because of road construction, or that you have a 2 p.m. meeting with a new client, or that you had a turkey sandwich for lunch.’

Now – this seems to me to be most important. It is widely accepted that – when living apart – it is necessary for each partner to establish their own independent life, rather than just to live vicariously on the absence of the other. I have no argument with this, but it seems to me equally important that these new separate existences are not fostered by a diminution of communication – as though contact would somehow taint or inhibit the new life – but rather by sharing its creation through a multiplicity of small contacts, much as would be second nature if actually living together. My fear is that to do otherwise could lead to growing apart.

Ms Morrison quotes Ben Le, an assistant professor of psychology at Haverford College in Pennsylvania who studies romantic relationships:

“The absence of a partner could, in the short term, result in a loss of part of the self. As the long-distance relationship persists, it’s likely that the self-concept would shift to account for that LDR — being a ‘person in a relationship’ would shift to being a ‘person in a long-distance relationship.”

Ms Morrison adds:

‘Missing a loved one actually involves something much deeper than wanting to be around them. Whether you know it or not, your relationship is an important part of your self-concept; when your partner leaves, you might—at least initially—have to redefine your sense of self.’

This is undeniable. I know that I am half the man when I am not with Kickass Canada Girl. My sense of myself is seriously diminished. I am less confident and, indeed, less capable.

Ms Morrison refers to the work of Greg Guldner, director of the Center for the Study of Long Distance Relationships in the US.

‘Guldner’s research shows that most couples tend to go through three phases of separation: protest, depression, and detachment. The “protest” phase can range from mild and playful—”Please stay”—to significant anger. Once an individual has accepted the separation, he or she might experience low-level depression, mostly characterized by slight difficulty concentrating, trouble sleeping, and the feeling of being a little down. “Unfortunately, that seems to be a reflex,” Guldner explains. “In other words, it persists. It continues with each separation and, in fact, sometimes worsens with each separation. There is very little one can do to prevent it.” Some people experience this in a more pronounced way than others. In the detachment phase, each person begins to compartmentalize his or her life, breaking it down into the sections with a partner and the ones without. It’s an effective coping mechanism that allows the individual to be in a relationship while doing what has to be done—until the occasional moment of weakness, that is.’

This captures – for me – the very real danger inherent in an extended separation. We can only hope that – by maintaining full awareness of what is happening to us – that the danger of the relationship suffering permanent change – or indeed damage – is minimised.

We are certainly working on that.

Recent Comments