“In Scotland, when people congregate, they tend to argue and discuss and reason; in Orkney, they tell stories.”

George Mackay Brown

There are many stories in and about Orkney – covering a great span of history. From the distant Neolithic past we moved forward to the last century.

During both the first and second world wars the natural deep water harbour that is encompassed by the Orkney islands – Scapa Flow – was a haven to the British Home Fleet. At the end of the Great War it also hosted 74 ships of the surrendered German fleet as the armistice negotiations dragged on. Believing that its ships would be handed over to other European nations the German commander – Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter – gave the command to scuttle the entire fleet in the Flow. A total of 52 ships went to the seafloor and this remains the greatest loss of shipping ever recorded in a single day.

Many of these ships were subsequently raised, not least because of the value of the steel therein. All steel produced since the Trinity atomic bomb tests in 1946 has exhibited a higher than previous level of background radiation as a result of the raised levels in the oxygen used in the smelting process. For some applications – such as the manufacture of medical scanners – this is not optimal, though since surface testing was stopped the levels have, apparently, been slowly falling again.

In the second world war the British battleship, Royal Oak, was sunk by German U boat, U-47, which had contrived to avoid the defences and to penetrate the Flow. Churchill immediately ordered the construction of further barriers to prevent any future such ingress, the which were constructed by Italian prisoners of war. Being a long way from home (and from their familiar Mediterranean climate) these captives asked – and were granted – permission to convert a Nissen hut into a chapel. This has subsequently been restored and is the subject of these photos:

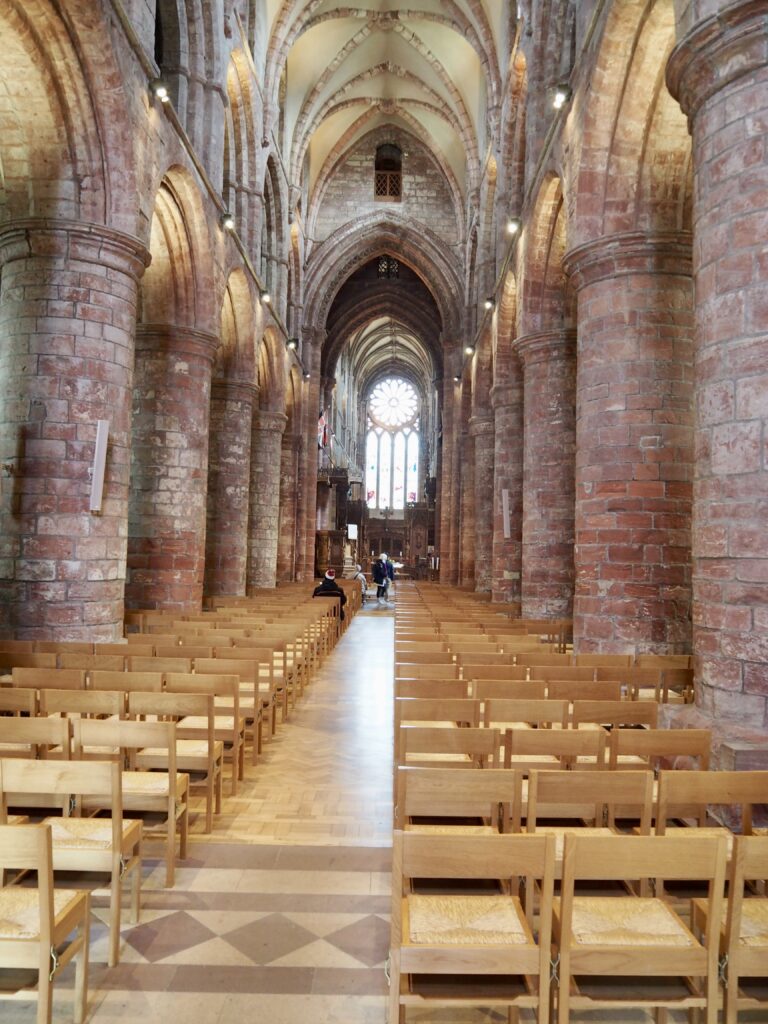

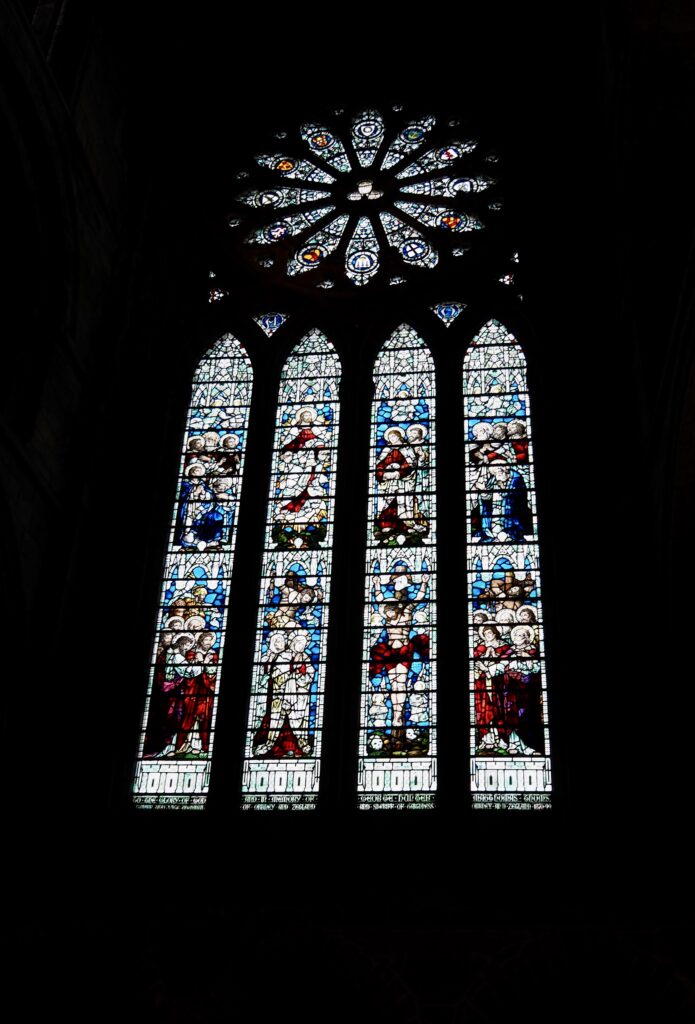

Whilst on this religious theme I should mention Orkney’s lovely cathedral – St. Magnus – which can be found in Kirkwall.

Whilst on this religious theme I should mention Orkney’s lovely cathedral – St. Magnus – which can be found in Kirkwall.

The story of St. Magnus is an interesting example of the intersection between a narrative – in the form of one or more written sagas – and what is recognised by the church to be historical and ‘religious’ truth. It seems inevitable that versimilitude lies somewhere between, but different folk clearly take from the different elements that which they need the most.

The story of St. Magnus is an interesting example of the intersection between a narrative – in the form of one or more written sagas – and what is recognised by the church to be historical and ‘religious’ truth. It seems inevitable that versimilitude lies somewhere between, but different folk clearly take from the different elements that which they need the most.

Recent Comments