In my previous post I posited the question:

In my previous post I posited the question:

Which advance in automotive engineering – had it come into widespread use sooner than it actually did – might well have completely changed the course of twentieth century history?

The answer – as I’m sure many of you knew – is… reverse gear!

Though the first production car to be fitted with a reverse gear – Ford’s ubiquitous Model T – made its appearance in 1908, it was some years before the application of this innovation became established practice throughout the world.

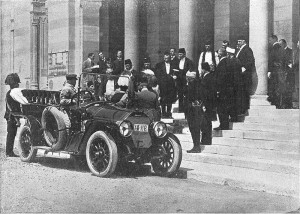

On 24th June 1914 the Austrian Archduke, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophia paid their ill-advised visit to Sarajevo in the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina, unaware that a group of seven young assassins – their bombs and pistols provided indirectly by neighbouring Serbia’s military intelligence service – lay in wait for them along the route that their motorcade was to follow.

Though several of the would-be assassins lost their nerve at the vital moment, one – Nedjelko Cabrinovic – did throw his bomb as the Archduke’s car passed. The missile bounced off the canopy of the car and exploded under the following vehicle, injuring several of those on board. The remainder of the motorcade continued to City Hall where the furious Archduke rounded on the Mayor of Sarajevo. It was decided that the visit should be cut short.

Franz Ferdinand – however – insisted on first visiting the hospital to which those injured in the explosion had been taken. The motorcade accordingly retraced its passage back along the Appel Quay – the route that the motorcade had already come but also part of the originally scheduled onward journey. Unfortunately the change of plan had not been communicated to the drivers and on reaching Franz Joseph Street, where one of the conspirators – Gavrilo Princip – was still stationed, the cars slowed and made the turn. On being alerted to this mistake the driver of the Archduke’s car braked the vehicle with a view to rejoining the chosen route. The car came to rest a short distance from Princip’s position.

Unfortunately, the car had no reverse gear – and thus had to be pushed backwards onto the Appel Quay. Princip had time to reach the vehicle and to fire the two shots that killed the Archduke and his wife.

Had Princip not been able to fire – or had his shots missed or only wounded the Archduke – Austria-Hungary would not have had a casus belli on which to go to war with Serbia. Had a fresh Balkan war not broken out the Russians would not have mobilised in support of the Serbs. Had the Russians not mobilised, the Germans – who had offered Austria unconditional support – would probably not have launched an attack on Russia’s close ally – France – aiming to remove them from contention before turning attention to the Russians themselves. Had Germany not violated Belgian neutrality to attack France the British would most probably not have become involved in what rapidly turned into the Great War.

Had there been no Great War it is highly likely that the subsequent rise of fascism would have taken a very different course and there may well not have been a second conflagration. Had there been no World War II the course of European history would have been very different. There might have been no impetus to develop nuclear weapons and the standoff between East and West that overshadowed much of the latter part of the century might never have occurred.

Who can tell? What is clear is that none of the European nations that allowed themselves to slide into the war in 1914 had set out with this objective in mind.

If you have not previously done so but now feel impelled – in this centenary year of the start of that lamentable conflict – to gain a clearer understanding as to how this unfortunate sequence of events unfolded, I strongly recommend Christopher Clark’s excellent ‘The Sleepwalkers’. Comprehensive, well argued and splendidly written, this volume cuts through much of the fog that surrounds the causes of this most terrible calamity.

“As it is with all stories, fast cars, wild bears, mental illness, and even life, only one truth remains: your mileage may vary”

“As it is with all stories, fast cars, wild bears, mental illness, and even life, only one truth remains: your mileage may vary”

Recent Comments